Source: Scott Adams

Introduction

One of my favorite statistics concepts to talk to people about is the asymmetric loss function. Aside from being a super-fancy sounding term, it provides (what I think) is some remarkably profound guidance on how to think about engineering, and occasionally life in general.

No formal background in statistics will be required to understand the concepts herein.

Let’s dive right in.

Engineering Application

The Concept

The “asymmetric loss function” refers to a very basic concept:

If you’re gonna be wrong, choose the best flavor of wrong.

Let’s illustrate this with an example.

Motivating Example 1

One of the classical ways to illustrate the asymmetric loss function is through an incoming missile detection system.

Problem Statement

Like it or not, countries can launch missiles at each other. These cause widespread distraction and sadness. Detecting missile launches is a key portion of most national defense strategies, as detection enables countermeasures to be taken to mitigate the impact of a missile attack.

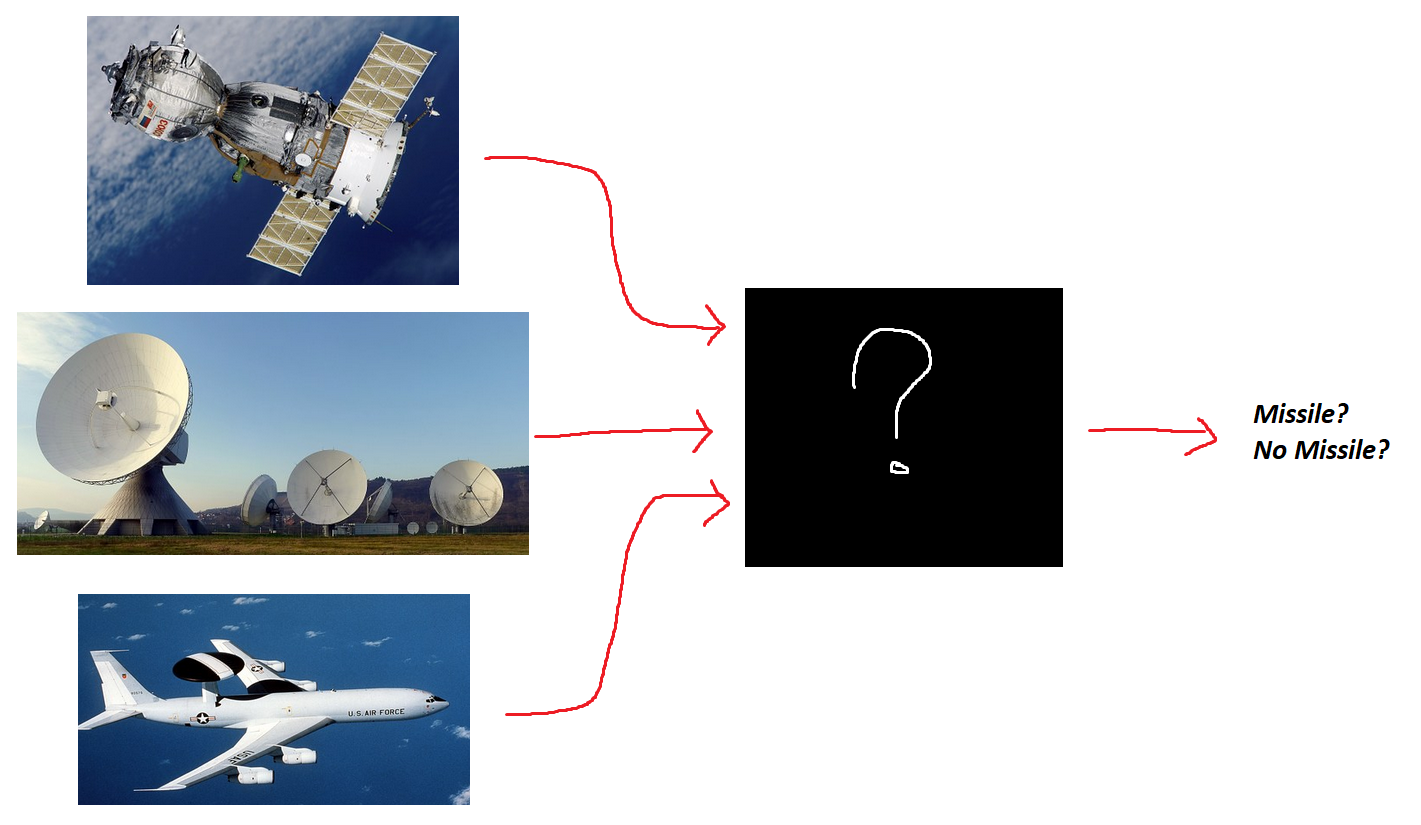

In general, such a system would have multiple inputs: Air, ground, and space based sensors would monitor the airspace, and provide information about radar & visual observations to a central system. This system would have to interpret all these inputs and produce a single, boolean output: Missile? or No Missile?

The “asymmetric loss function” deals with how we design the contents of the black “?” box. Clearly, it’s not going to be a trivial transformation.

We’re not going to discuss exactly how to design the contents of the box, but rather part of the the philosophy that the box needs to be designed with.

Real-World Expectations

As you’ve probably seen from robotics, real-world conditions aren’t exactly ideal.

Sensors have noise. Sensors can fail. Objects can get in the way of the thing you care about, and screw up your readings. The same reading from a sensor may indicate two completely different things. Sunspots can inject random voltages at random points in your circuitry. Joe Freshman can come around with a hammer and smash your system to smithereens. You have many obstacles to accurate detection. Making a black box which always works will likely be impossible.

Therefore, you are likely, at some point, to make a wrong guess.

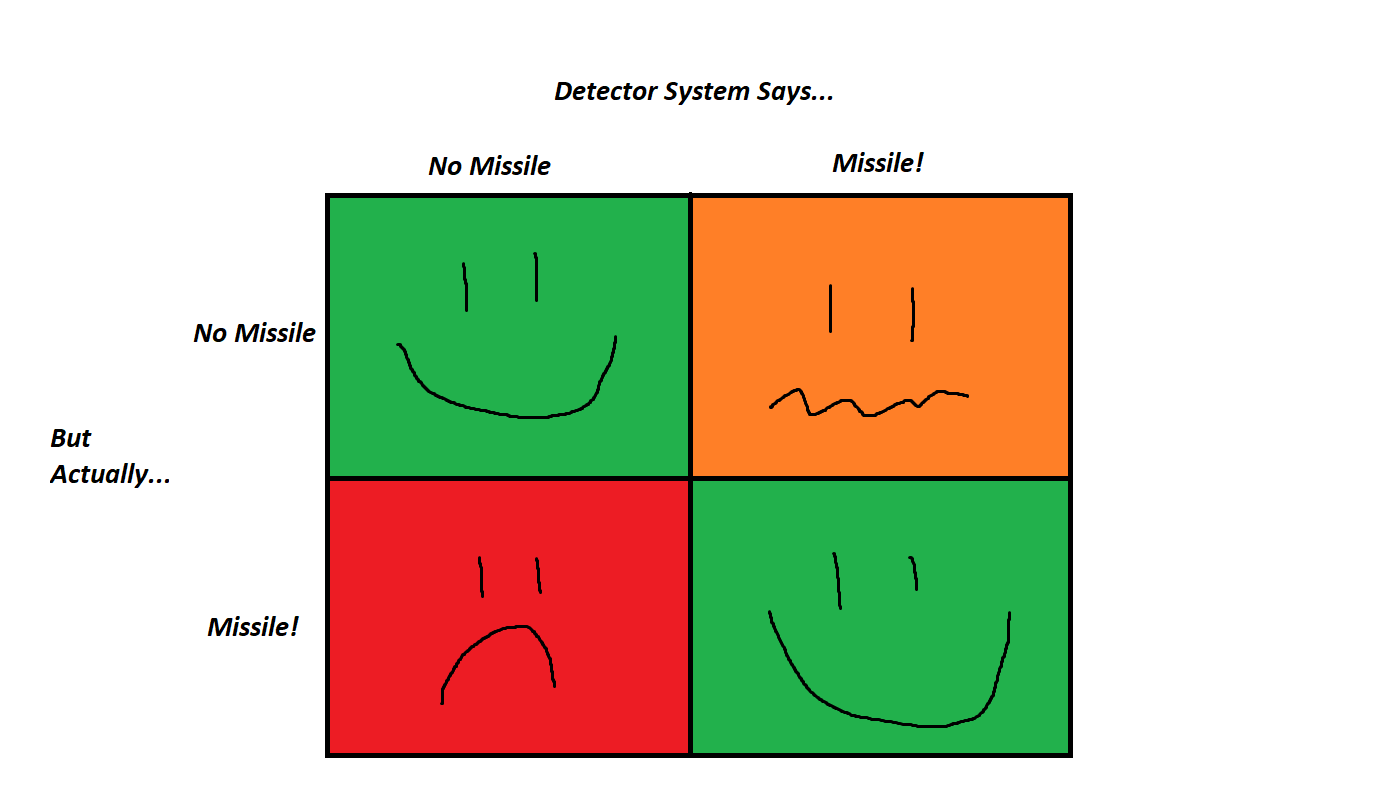

It’s important to note that there are two flavors of wrong here.

On one hand, say there is no missile, but something causes your system to report that there is in fact a missile. This is called a false positive.

On the other hand, say there is in fact a missile approaching, but something causes your system not to detect it. This is called a false negative.

In one handy-dandy chart:

The point of this (fairly morbid) example: The two flavors of wrong are not equally bad.

In the case of a false positive, you’ll have to wake someone up to go look at the situation, and maybe launch some countermeasure airplanes or chaff or something. However, within a short time, you’ll likely figure out that there wasn’t any threat to be had, and all will go back to normal. Some money spent, but no one’s permanently harmed.

On the other hand, if you produce a false negative, you get blown up without ever knowing what hit you. Boom. Dead. Bad.

Clearly, while designing such a system, you’ll want it to “err on the side of caution” as people usually say. In this case, that means to lean toward “Probably a missile!” whenever your detection is a bit unsure. This will help avoid the very-bad false negatives.

Boy-Who-Cried-Wolf Effect

Separately, it’s worthwhile noting that lots of false positives over time will lead people to distrust the system as a whole, and ignore its warnings (even if there actually is a missile coming in). The same actually applies for false negatives, though for how we’ve constructed our problem statement, you only “get” one false negative before you’re dead.

When designing systems, it’s important to keep this in mind - the people looking at the output need to be able to trust the output, otherwise the system won’t be useful.

Motivating Example 2

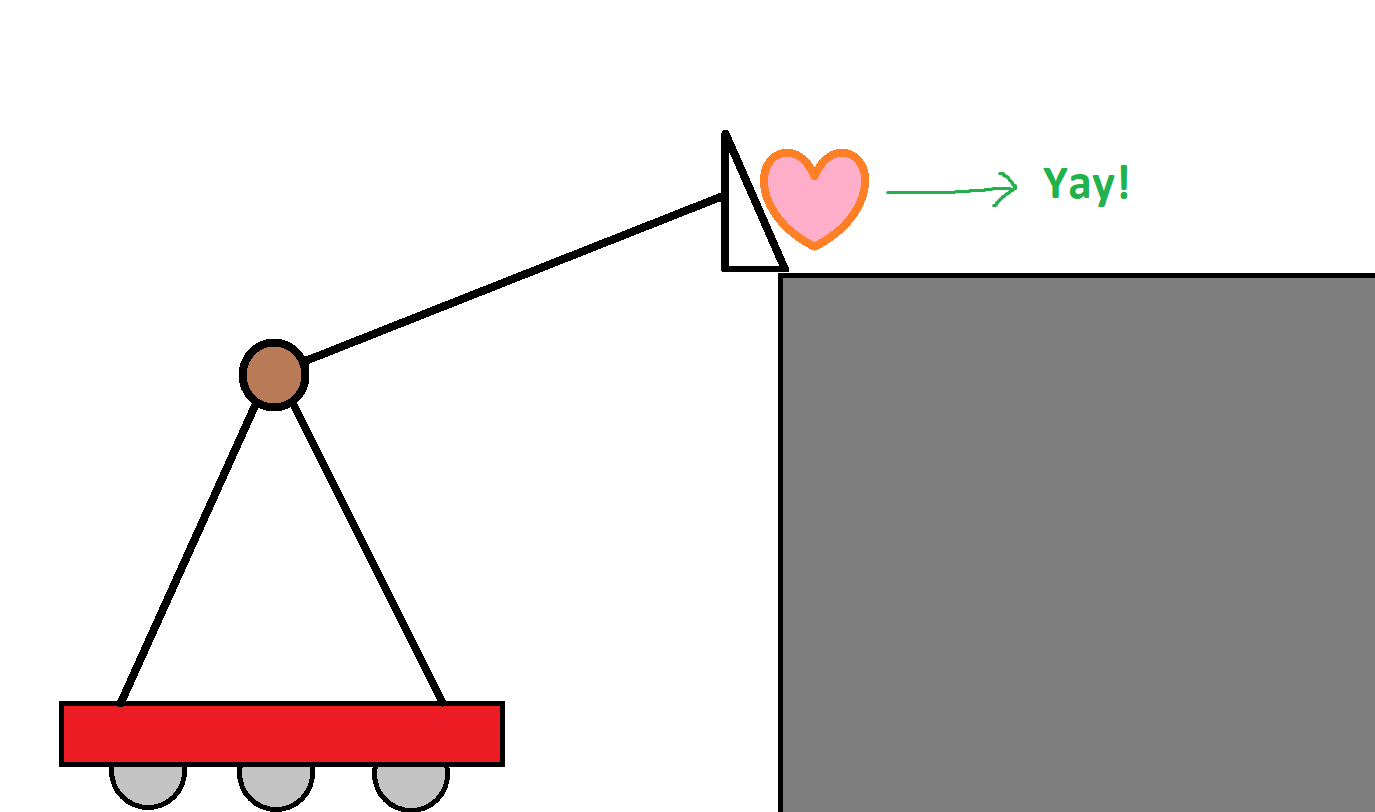

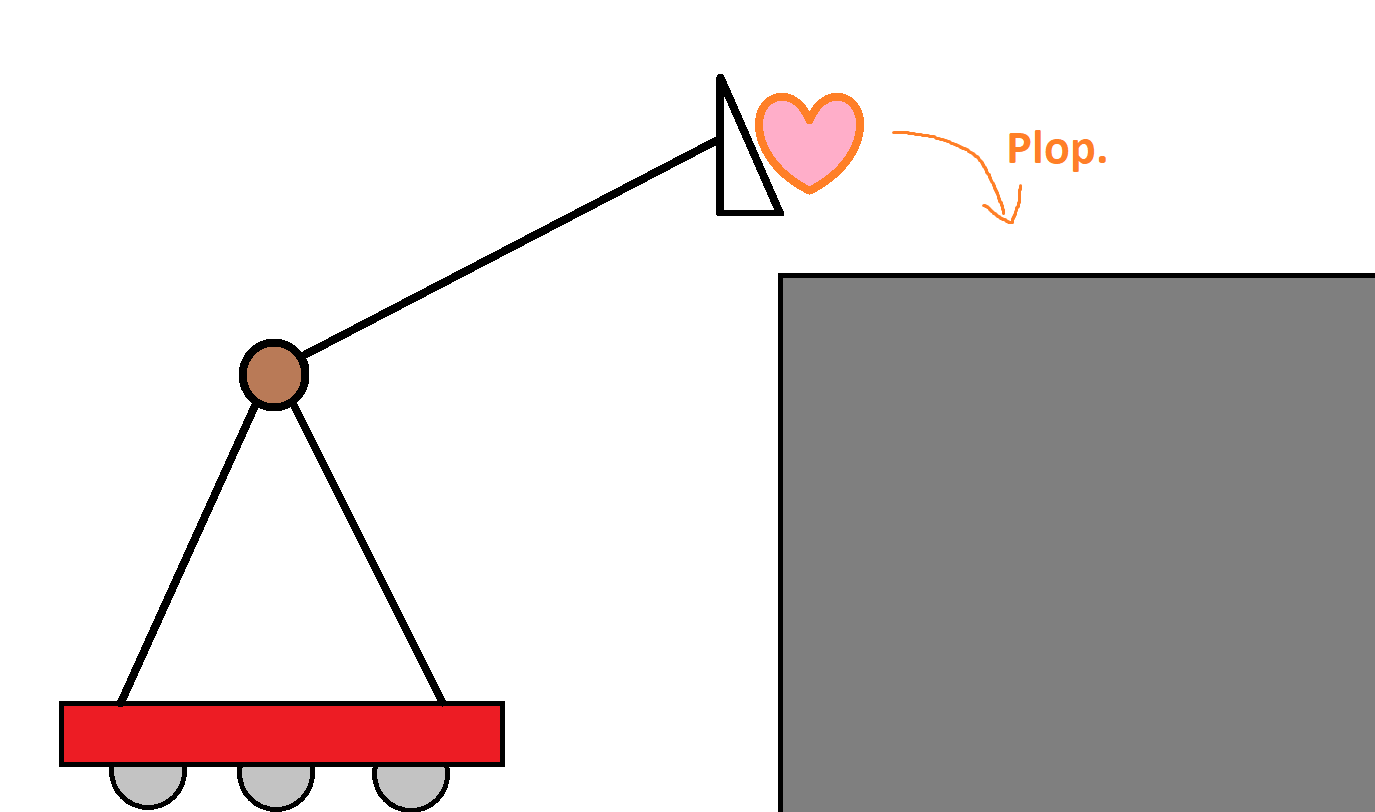

Let’s look at something a little less morbid: Let’s look at an arm on a robot, which is supposed to deliver a gamepiece to a goal which is on top of a shelf. Something like this:

You can see that the triangle shovel on the end of the arm is responsible for lifting the heart gamepiece to the goal level. When the gamepiece is just barely high enough, the gamepiece is quickly delivered horizontally to the goal.

Again though, real world effects come in. Let’s say we end up with an arm that’s slightly too high.

In this case, we’re OK still. The arm being too high causes the gamepiece to drop slightly onto the platform. Assuming it can’t roll off and isn’t fragile, we’re still ok. The extra height leads to inaccuracy in placement, and takes longer to move the arm, but overall we still accomplish our goal of delivery.

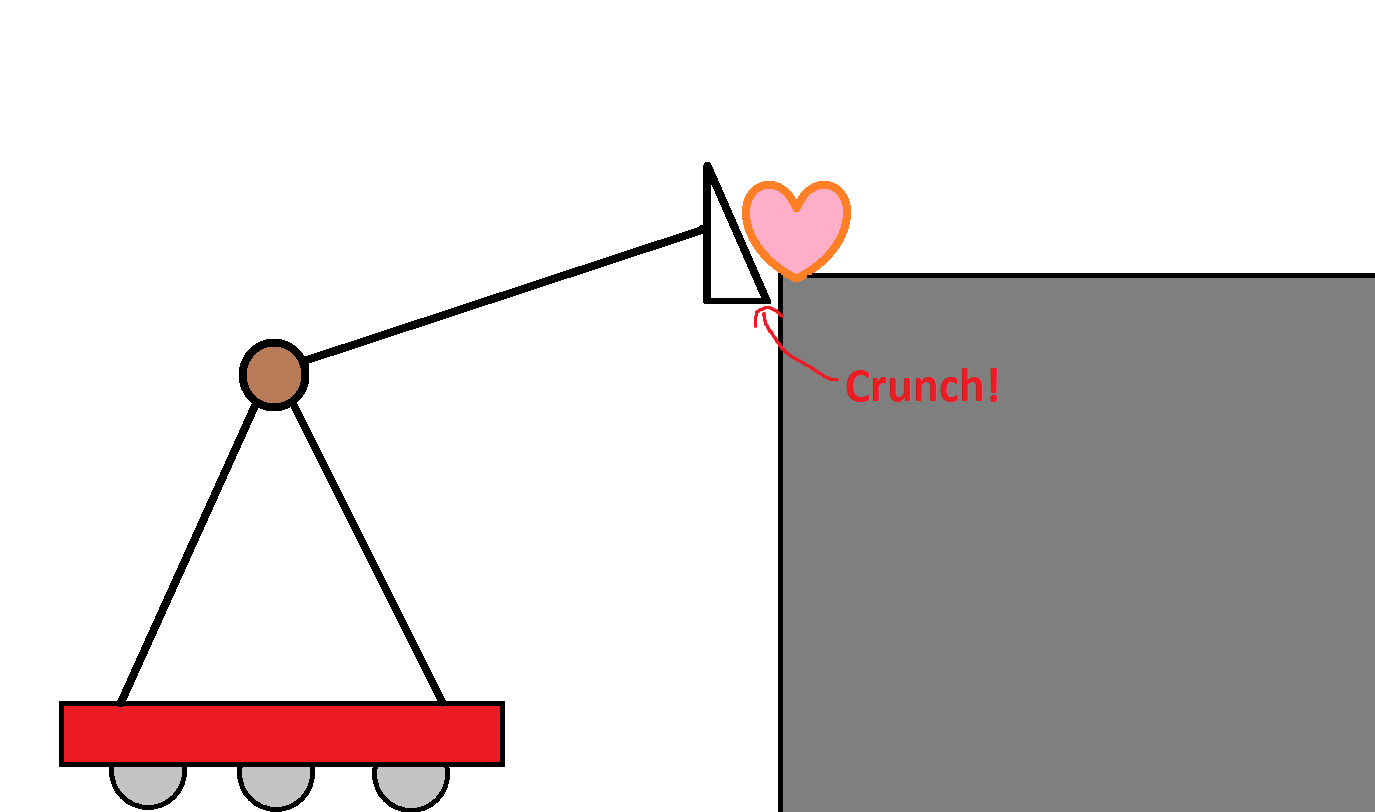

However, things get nasty if the arm is too low.

It fails to deliver gamepiece to the goal. Additionally, the arm itself crashes into the support structure, causing damage to the robot.

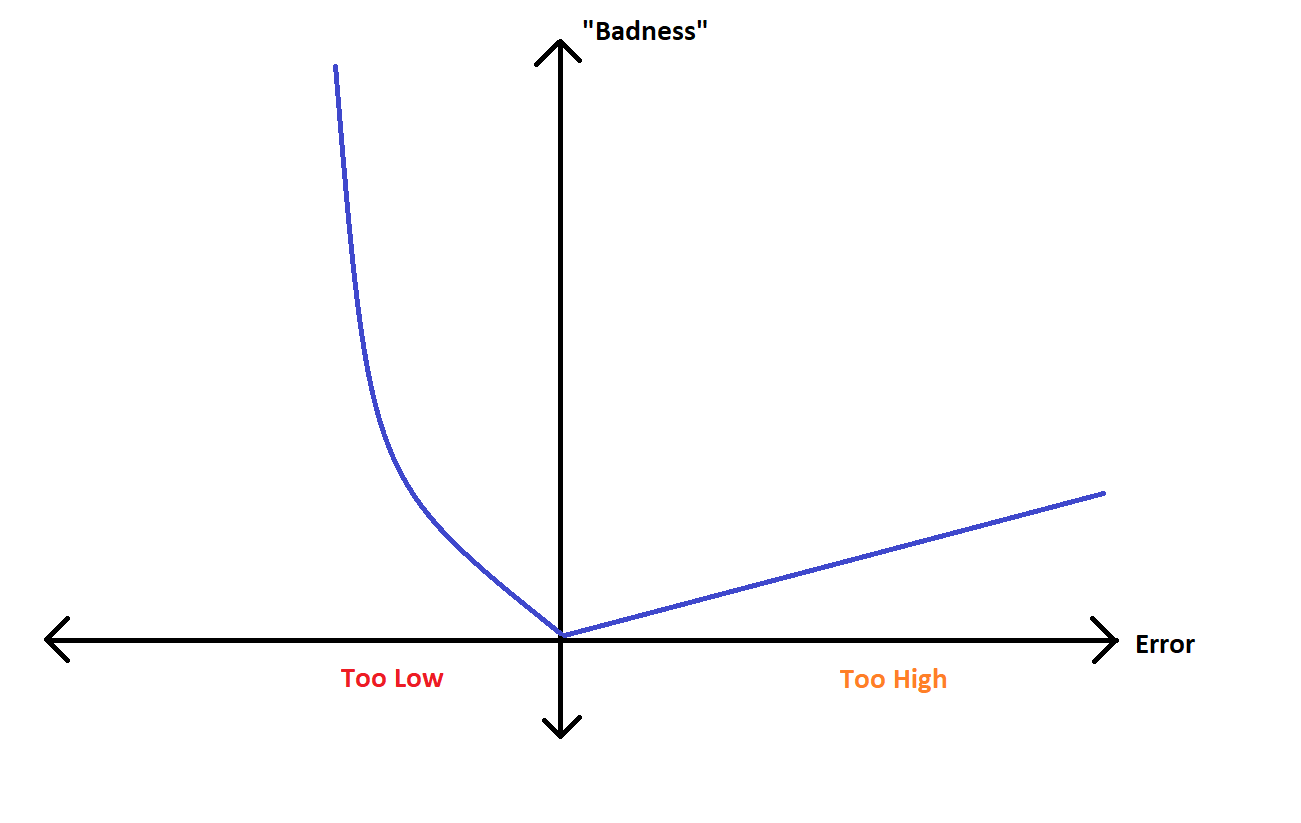

Obviously, if we’re gonna be wrong, we want to be slightly too high, rather than slightly too low. If we were to create a mathematical function to describe this, and plot it, we might produce a graph that looks like this:

All we’re doing here is making up some numbers to describe the idea that “too high is bad, but too low is worse”. You could definitely assign some real numbers, in terms of the monetary cost of destroying your robot, or the emotional cost of seeing your team lose a match…. maybe… It’s usually pretty hard to make it really accurate. But accurate isn’t the point here, it’s more-so about massaging your engineering knowledge about “what flavor of wrong is least-evil” into a mathematical function.

When you construct this function, you have created what is formally known as a loss function - any mathematical function that describes “badness” as a function of error. Indeed, the one that we are looking at right now is asymmetrical because it doesn’t look the same on both sides of the Y (“badness”) axis. This visual asymmetry in the graph is what communicates “some flavor of wrong is better than another flavor of wrong”.

Why create this function, especially if you’re just making up numbers? Well, maybe you don’t always have to. It is useful to be able to draw the picture to talk about your goals while designing the robot. Knowing and understanding this picture is what can help inform how you tune your PID algorithm controlling the arm position (In this case, you may want to purposefully overshoot the goal slightly). Or maybe how you do your tolerances in your mechanical design (ie, skew-up is better than skew-down). It helps you know where redundant sensors might be needed, versus where they’re not as critical to have.

Also noteworthy - many modern control theory topics discuss the idea of an optimal controller. Here, the definition of optimal will have to vary use-case to use-case. But mathematically, all will assume that you can describe this “loss” or “cost” function to inform the controller what things are good, versus what things are ok, verses what things are really bad.

Life Philosophy

I also think these topics apply to life in general. Maybe it’s not super profound, but worthwhile to consider for a bit. Some time, in your life, you will be wrong. That’s ok. However, if you want to mitigate the bad effects of being wrong, choose the cautious path which results in less badness.

Hedge your bets. Clearly state your assumptions. Ask for others to help verify your work. When you are wrong, doing things like this help you achieve a “better flavor” of wrong.

It’s almost always better to be able to say “Yes I was wrong, but here was the full thought process I went through, and all the work I did to try to not be wrong”. Far better than “Well, I’m wrong, and I didn’t lift a finger to even attempt to be right”.

Conclusion

Again, analyzing the loss function for various parts of your robot won’t exactly tell you how to design it - it will just give you insights into which designs are better or worse. Just one more tool for your design technique toolbox, hopefully to help discover issues in advance, and design around them.