Introduction

When I started writing this blog, I didn’t have much in mind. I was mostly hoping just to write some text, and make it available on a website. It kinda snowballed over time - it’s still not super complex, but does incorporate a number of different web technologies. For anyone interested in doing something similar, or just curious, I figured I’d document what sorts of technologies I’m using currently.

Jekyll

Jekyll is a static website generator. Website generators, in general, are tools which allow you to enter in a relatively small amount of information (for example, the text of a post) and create nice-looking and well-structured HTML (which your browser can display) in a scripted manner.

They’re one of many software tools that take a form of information that is easy for humans to manipulate, and transform it into something which is easy for machines to work with.

This lets us have our cake and eat it too - pages are easy to make and change, but still look nice, and minimize the work done by the client computer to display the content

A static website is one which has the content pre-defined, and served the same way to all users.

A website like Facebook or Twitter is the anti-example to this - depending on who you are (as determined by who is “logged in”), and what friends you have or which handles you subscribe to, the contents returned to your browser when you visit “facebook.com” or “twitter.com” will vary greatly. In order to make this happen, they have to dynamically generate the HTML, Javascript, and CSS files which are sent to each client on connect.

However, for many sites (including this one), there’s no mechanism for login, or differentiating users from each other. Each person who visits gets the exact same set of blog posts. Therefor, there’s no need (or reason) for dynamic generation of content. We can pre-generate the exact HTML, Javascript, and CSS you will receive, and just hand it off to you when you ask for it.

This is a much simpler way of doing things, and is therefor more limiting. I don’t really have the ability to change what each user sees. However, based on the whole point of a blog in general, that sort of flexibility isn’t needed. Flexibility usually implies complexity, which implies more work. To keep the whole thing simple, I chose to go with a static website, and keep things simple.

Jekyll was chosen specifically because it integrated well with Github, which was my hosting platform (will explain soon). It turned out this didn’t matter too much, but was important at first.

Github.io - Hosting

Every website, fundamentally, works the same way:

- A client computer contacts another computer and says “Hey, I want to see XYZ webpage”

- The server says “Sure, here’s the files associated with XYZ”

- The client computer displays the files.

To do this, it’s required that there is some server, somewhere, accessible to everyone in the world, which not only stores the files associated with the website, but is configured to properly format and provide responses to clients when requested.

Designing this server is a big key to having a well-working website. It has to be always-on - any time you turn it off, the website “disappears”, and is inaccessible to everyone. Additionally, it will have to do work any time someone else in the world asks for the website. This means that the load is fairly unpredictable. Between these two facts, using your desktop or laptop as the server is generally a bad idea. You’ll want a dedicated, separate computer that you can leave on all the time, and not care if the CPU load spikes randomly.

However, even if you were to have a separate computer, hosting your own web server is hard to do right. For one thing, you have to update your network’s firewall to allow external people to send commands into the server. This reduces the security of your network overall, and is a prime target for folks looking to hack into your network. Without careful security measures, you risk exposing every device on your network to the prying eyes of malicious hackers. These points of entry may be in your router and your network configuration, or in the server itself - old, buggy software on the server is a great way hackers can exploit their way into your personal files, take control of your website, and generally wreak havoc.

Furthermore, most consumer Internet Service Providers don’t allow you to host a website from your connection - you usually need a business (or otherwise special) agreement to have them allow incoming HTTP connections to your network.

For all these reasons, when hosting a website, it’s often easier to let someone else do it for you.

Enter github.io. This is Github’s free service for hosting static websites. It’s pretty simple - create a special repo to house your website. Push the content to the website, with a special file named “index.html” as the “top-level” file which is served whenever someone visits your website.

It’s an awesome system actually - the only real skill the developer needs is git. As long as you can push your files with git, you can allow github to serve them as a website to anyone in the world who wants to visit the website.

Given that the hosting was free, it seemed like an easy choice.

Google Domains - the Web Address

Even once a website is available on some server on the internet, visitors still need an easy way to find the server amongst the many, many servers online.

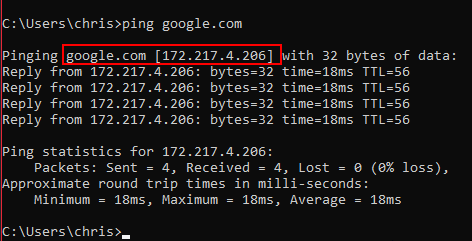

Each server online does get assigned an IP address. Just like on your robot and the driver station get an IP address (10.TE.AM.XX), the server gets a public-facing unique IP address. For example, www.google.com will point to a wide range of addresses, depending on where you live.

However, remembering these number combinations is intuitive, and hard for humans.

This is where the “Domain Name System” (or DNS) servers come into play.

DNS servers are a handful of servers that know about other servers. They maintain a mapping of convenient english names (like “google.com”) to actual IP addresses. They do fancy things, handing off requests to each other, until the lookup of website name to IP address has been completed.

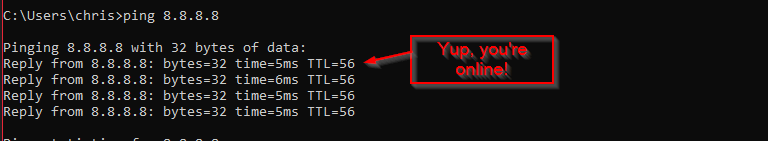

The servers are distributed, and live at fixed and well-known IP addresses. Most ISP’s have their own. Google does too (8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4), and 1.1.1.1 is another up-and-coming one.

As an aside: an easy way to check “Am I connected to the internet” is to ping a known DNS server. If the IP address 8.8.8.8 responds to pings, you know your network allows for connection to the broader internet.

By default, Github provides a URL for free for your website, but its name is not configurable: mine would be “gerth2.github.io” - which, though nice, is not informative about the content of the site.

In order to allow for the name of the website to show up as the URL, I pay $12 per year to Google Domains. I used their service to purchase and maintain ownership of the domain name “trickingrockstothink.com”. In return for my payment, they keep their DNS servers configured such that anyone who types “trickingrockstothink.com” into their browser URL window will get redirected to the IP addresses associated with Github’s web host servers, and specifically my website.

Markdown

As stated previously, the point of using Jekyll as a website generator (rather than manually writing HTML) is to allow me to enter the information (ie, the text you’re reading right now) in the most rapid way, and letting a script do all the “HTML Decoration” around it in a algorithmic way.

Jekyll takes a few input formats, but Markdown is the most common. Markdown is one of many, loosely-defined “markup” languages. A markup language is not really a programming language, but rather a set of special character sequences to indicate a desired formatting. For example, if I want italics in some text, I have to wrap the text in underscores, _like this_. Jekyll’s markdown interpreter knows to place the text inside the _ _’s inside of HTML and CSS blocks which cause the text to go slanty. Similar character sequences are recognized for footnotes, bold text, section headers, and many other things.

Again, there’s no concrete reason I couldn’t just write the HTML. But, it’s a lot more keystrokes to get the exact same output.

Additionally, I like the fact that markdown source files are really easy to read as a human. Even if Jekyll and markdown disappear off the face of the planet tomorrow, it would be pretty trivial to move them to some alternate markup format. HTML in theory could be the same, but it isn’t nearly as straightforward.

Add-ons

Obviously, Markdown doesn’t allow for unlimited configuration of how your text looks, and that’s on purpose. It sacrifices flexibility to make the most common operations really really easy. However, as we’ll show, there’s still plenty of opportunity to extend its functionally as needed.

Chart Plotting

Certain concepts are much better explained with a 2-D graph, rather than words. Especially in the PID tuning, math intro, and similar posts, it’s crucial to have the ability to draw graphs easily.

I’m using a javascript library called D3JS. A nice part of markdown is that it supports the concept of injecting custom HTML midway through a post.

For example, I can create the following chart:

Using the following javascript:

//Create an empty DIV to be populated with the actual chart

<div id="plot2"></div>

//Define a tiny bit of javascript to configure the chart

<script>

functionPlot({ //Special function that D3JS has to create a plot

target: '#plot2', //Puts the plot onto div named "plot2" (see above)

title: '',

grid: true,

yAxis: {

label: "Pressure (psi)", //Y axis configuration (for pressure)

domain: [0, 150]

},

xAxis: {

label: "Time (s)", //X axis configuration (for time)

domain: [-3, 20]

},

data: [{

fn: 'max(0,120-120*exp(-x*0.3))', //Equation which is actually plotted

title: 'Tank Pressure'

}]

})

</script>

By putting this code literally just into the markdown, we can create some nice looking plots!

D3JS supports both a symbolic definition of the equation (as above), as well as a point-by-point definition. If you look at some of the PID simulation javascript, you’ll see where each point on the graph is calculated based on the plant model + controller simulation. In turn, these points are passed to D3JS to actually draw the plot image.

Highcharts is another super awesome plotting library - it’s much more interactive and a bit heaver-weight than D3JS. We’ve used it quite a bit on data viewers on our robot. I might eventually move this website over to use it as well.

Math Formulas

Aside from displaying 2D plots of graphs, it’s also super useful to create formulas, like this one:

Latex is the industry standard for typesetting research papers, as well as the formulas they contain. It was invented by Don Knuth, one of the great minds of computer science in the 21st century. It was one of the first viable “markdown” languages. It’s not super intuitive to use, and is often a bit confusing - it follows a “what you type is what you get”, rather than a “what you see is what you get” (WYSIWYG) paradigm, which gets wacky when typing out instructions while visualizing what they actually mean. It’s the opposite of Microsoft Word, a WYSIWYG editor.

The choice of word “Typesetting” is very deliberate - Latex is a text-based language for describing what a document ought to look like. You rely on the computer to do the actual generation of the real thing.

Still, it’s super powerful. I used it to typeset my resume, and a handful of different not-really-for-academia-but-academic-style papers.

Also, there’s this thing called Mathjax online. It’s a simple javascript plugin which uses the special character $ to identify text which ought to be interpreted as Latex markdown, not normal markdown.

For example, the formula above was created with the text $$ f(x) = \frac{25x^{4}}{1114} $$.

Anyway. My personal opinion on Latex: I feel like its ripe for replacement. It’s a bit obtuse how it works. Modern markdown languages are much simpler. However, it’s by far the best thing out there to do what it does (typeset math formulas and associated academic papers). I’m not entirely sure how it would get improved without destroying that functionality. Due to that, I predict (just like regular expressions), despite any clunkiness at first glance, it’s here to stay.

Development Flow

If you want to take a look at how the blog gets developed, go ahead and clone https://github.com/gerth2/gerth2.github.io onto a folder on your local PC (or go look at it on github).

Obviously, I have to test that posts look right and are proofread and all the interactive parts are functional, prior to making them public online. To facilitate this, there are two main branches in the repo:

devis the branch with the source code, where I make and test all changes to the websitemasteris the “production” branch, containing only the public-facing HTML source that is served to client PC’s.

If you ever want to preview a blog post before it goes live, just keep track of the dev branch - I usually push to it before deploying to master.

On the dev branch, under the _drafts folder, you’ll find the .md files which are the drafts of posts I’m currently writing.

Generally, I’ll create a post in _drafts, write it out and proofread it, and perform any interactivity testing, committing and pushing as I go.

Once I’m happy with the post, I’ll copy it to the _posts folder with the proper date prefix, do one last proofread, test with a non-drafts test server, then run the deploy script.

To expound on these various components:

Drafts & Local Server

Jekyll supports running a webserver locally, to view your processed .html files just as though they were live on the computer.

On the dev branch, you’ll see two batch scripts:

serve_local.batserve_local_drafts.bat

Both build the website and launch the local Jekyll server on the results. The two are mostly the same, except that the _drafts.bat one has extra flags to tell Jekyll to include .md fields from the _drafts folder.

A nice feature of the Jekyll server is that it watches the local .md files for changes, and rebuilds the website as needed. This means my net development flow becomes:

- Launch

serve_local_drafts.bat - Create/edit a new draft post

- Load

http://localhost:4000in a web browser, and navigate to the draft post - Proofread & iterate on the

.mdfile for the post, refreshing the webpage whenever new changes need to be viewed. - Save the file and move it to the

_postsfolder - Close any running server, and launch the

serve_local.batserver - Ensure the “new” website is exactly as I want it at

http://localhost:4000 - Stop the test server and deploy to production.

Deployment Script

There is an additional script called deploy.bat which performs the deploy to production operation. In my case, “deploy to production” implies “build a fresh copy of the website, and make it available on the internet”.

It should be known that Github.io has the ability to automatically build Jekyll files to a website, and deploy them for you. All you have to do is push on master, and the build happens in the background. However, it has a key limitation: there’s very few Jekyll plugins that the Github servers will accept. I have a custom plugin to allow me to include code files from other directories - it was super useful during the x86 assembly blog posts.

Due to this custom plugin, Github won’t build my page for me. This means I have to do the following:

- On the DEV branch, check that all file changes have been committed

- Run the Jekyll command to build the website from

.mdfiles to.htmland friends. The output lands in the_sitefolder. - Commit the new webpage to the master branch, using the

git subtreeoperations to select just the_sitefolder. - Push the master branch. This makes the new website version public, and available to everyone in the world

All this action is contained within the deploy.bat script. This is the script I run after I’m “done”, and ready to make the changes public.

Miscellaneous Development Techniques

Admittedly, there’s not a ton of other advice I have. I’m an embedded engineer by trade, so running a website is definitely a bit outside of my comfort zone. I’m absolutely certain someone with experience in web development would happily comment with “aggressive suggestions” on doing things differently, and they’d definitely have a better way of doing things than I have. Good thing I’m not good enough at websites to implement a comment section.

One final thought, on a tool I use occasionally - Placekitten.com is an adorable way to create image placeholders of a specific size. This is for cases where you have to develop the website layout and interaction before you have all the content, and just need an image of a certain size. Using it is simple: Just reference their main URL with arguments to indicate the width/height of the desired image in pixels. BAM. They return and adorable kitten of exactly the right size.

For example, here’s http://placekitten.com/200/300:

DAWWWWWWWWWW.

Cookie Collection and GDPR

So - a key thing that’s actually kinda unique about this website - I collect exactly zero cookies. That’s right. Zero. Nada. Zip. What is this, 1995??

GDPR is the set of European Union regulations that govern how websites must inform you when certain pieces of data are collected. To be honest, I do like the concept overall. I do think consumers should be at least made aware of how websites are tracking them, and why.

However, as I read the regulations, my understanding is that, at any time, an agent of the European Union could contact me and ask me to produce a record, proving that every single visitor to my website was “properly” notified of the data collection I was doing. Doing so is not something I trust myself to be able to do.

I’d really love to use something like Google Analytics to track who is reading the website, and from where. It would help me determine my audience, how popular certain posts are, and what sort of impact new posts or changes to posts has. This would be very useful for me, the content creator, to create more meaningful content.

However, using Google Analytics means storing cookies on your computer, which means GDPR applies. And here’s the issue: I’m not a lawyer. I don’t really know for sure what I do and don’t need to do. And even if I get it right, if I’m ever questioned, I’d need to hire a lawyer to help me in court. And fly to the EU to discuss it with them. All this is expensive, and not something I’d particularly enjoy doing.

GDPR has no “oops sorry, I got it wrong, I’ll fix it” clause. There’s no warning. If you get it wrong, you owe the EU a ton of money, up to €20 million.

I do have a good job at the moment. However, I don’t have the kind of cash for EU reparations, or a lawyer. This website is only a community service. I can’t dump thousands of dollars into it - its just not worth it.

Therefor, I turned off all tracking of all sorts. Zero cookies should be stored on your computer. If you find one, let me know, I’ll turn it off.

If you do have feedback on any content on the website, please let me know at the email at the bottom of every page, or on ChiefDelphi.com.

If you are a lawyer with experience in Tech and GDPR and are willing to provide your services pro-bono, let me know as well! I’d love to add some extra features here with legal guidance. I would happily advertise your firm here, along with one or more posts about our experiences together.

Conclusion

Well, that’s about all I’ve got. Hopefully you’ve learned a tiny bit about the internals that make this website tick, and maybe some info for helping you make your own website.

Merry Christmas, Happy Holidays, and talk to ya next time!