“The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don’t know.” - Albert Einstein

Methodologies for Thinking about Big Problems

The world is full of huge problems. Lots of folks would say these require huge solutions. I’m not so sure.

As humans, there is a finite amount of information we can process at once. You may notice that really smart coworker or kid in your class who can seemingly process, memorize, and store vast amounts of information. They might be good,butr they too have their limits.

The problems we get asked to solve are frequently larger than we can contemplate “all at once”. They’re too big to keep every fact, detail, and item in your head at once, and to contemplate every relationship.

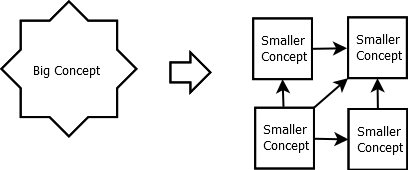

When it comes to big problems, you have to break them down into smaller problems to deal with effectively.

When you are in school, your good teachers are actively doing this for you. By presenting material one day at a time, and in a well-defined sequence, they lead you through a logical sequence of steps to the final answer. As you move out to do more self-learning, you get to do this on your own!

A Concrete Food Example

Let’s say that you are tasked with cooking a beautiful roasted chicken dinner. You know your guests are expecting a great meal, but they aren’t going to concern themselves with the details of how it came about. They interface with you by receiving the food, and you know you must provide the food, however you are responsible for the details of how to make it.

Furthermore, you’re probably going to use some ingredients to make the food. For example, carrots and onions go great when stuffed inside a whole chicken. Let’s say you purchase these from a local farmer’s market. You interface with the farmer by exchanging money for veggies. The farmer doesn’t need to care where the money came from, nor do you need to care exactly how the farmer planted, nurtured, and harvested the produce. All you need to do is know the common interface format, and you both get what you were looking for.

Everyone in this story has a small part to play, with well defined interfaces to each other. No one person has to think about the whole process at once.

The key takeaway is this: solving big problems requires breaking them down into their components, and focusing on one component at a time. Effective problem solvers learn the skills (perhaps even artistry) of breaking down a big problem into smaller ones.

Subdividing and Abstraction

As we start on this adventure of learning about computer systems, abstraction is the first vocabulary term to learn.

An abstraction is a particular way of breaking down a big problem into smaller problems. More specifically, to abstract a particular concept is to remove all extraneous details about the concept, and focus in only on a very select few of interest.

Slice N Dice

Practically, the software engineer’s job starts when they divide a big problem into small ones, with relationships between the concepts.

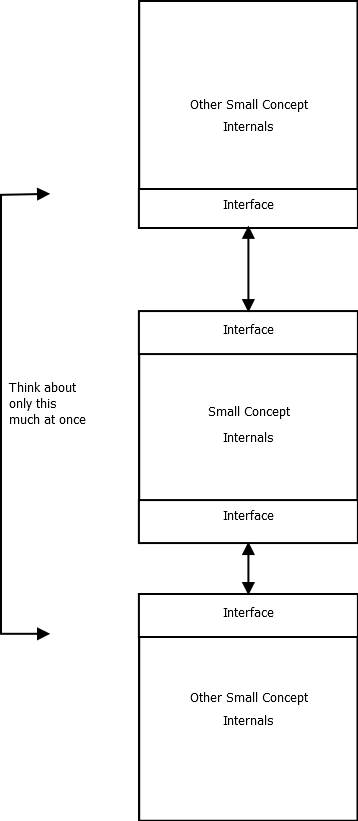

For each small problem, divide it into “internal concepts” and “interface concepts”.

The “interface concepts” of each small problem form the abstraction of that problem - they boil the small problem down to just the critical details required for solving other small problems.

Why do this?

It allows you to analyze each small problem individually. Rather than think about the whole big problem at once, you instead pick a single small problem and consider:

- The internals of the just that one small problem

- The interface of the just that one small problem

- The interfaces of other related small problems

This technique works well under the following assumptions:

- Interface layers are as “thin” as possible - ie, you reduce all but the absolutely most essential info

- Internals are right-sized

- The number of inter-small-problem connections is right-sized

Right-sizing Internals

This is why the subdividing and abstraction process often has a bit of “artistry” to it.

If you make your divisions too small, each small problem ceases to have meaning on its own, and cannot be analyzed without context of the full problem. This defeats the purpose of subdividing.

Conversely, if you make your divisions too big, each small problem becomes prohibitively complex to analyze by one person, again defeating the purpose of breaking it down.

Exactly what the correct size is varies depending on the person solving the problem, how familiar they are with the subject matter, how much coffee they’ve had today, and numerous other factors. The good news is that the division doesn’t have to be absolutely perfect to help you create better engineered systems, and there are often many “good enough” answers. Furthermore, if you play your cards right, you can often re-do the problem division in the future, as you learn more.

Conclusion

Abstraction, without concrete examples, is by definition an “abstract” concept. Don’t let that worry you - we will hit plenty of relevant examples in the coming posts.

Simply remember that when we talk about abstractions, we’re talking about removing details we don’t care about, to focus on the small parts that we do.

The world is full of huge problems. Lots of folks would say these require huge solutions. I say they require lots of small solutions, linked in just the right way.

Next Steps - Where are we going?

Before we get into software specifics, we’ll do some theoretical background. Start with the Math Primer.