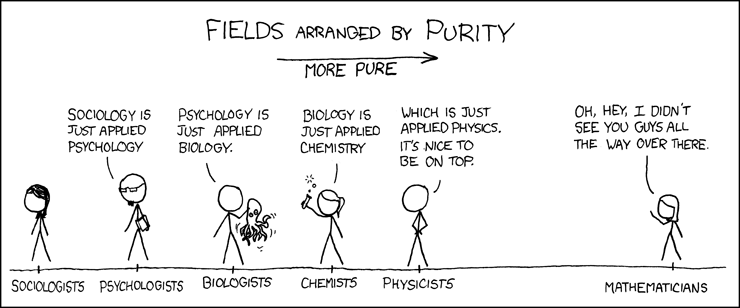

source: xkcd.com

source: xkcd.com

Despite many jokes, engineering and math do indeed have a very strong linkage. Some say that mathematics is the language through which science is expressed. Since engineering is relies strongly on science to execute new technology, any engineer should have the basics of mathematics as the foundational tool in their toolkit.

The good news is that, for the purpose of understanding most of the basics of software, only the basics of a few different fields of mathematics are required. Precise computation techniques can be useful, but first and foremost a conceptual understanding is required.

The goal of this post is to go over some of the basic math concepts we’ll be using as we go forward. Deep knowledge will not be needed - we’ll just hit the basics of the concepts we’ll be using later on.

The Basics

Algebra & Functions

Algebra is the branch of math that most students start with, early in 9th or 10th grade. Fundamentally, it studies the abstraction of specific numbers into variables (denoted with letters, such as or ). Algebra defines laws and requirements for how variables can interact with each other. Rather than being locked into only a specific “use-case” of a set of measurements, Algebra allows you to talk about many different scenarios all at once.

This allows us to define equations to show relationships between different physical quantities, and manipulate those equations to learn about new relationships that may not have been obvious at first. Usually, we will want to calculate a certain value, given a set of input values. Algebra is useful in manipulating known equations into a form that has the output on one side of the equation, and all the inputs on the other.

This is the basis of a “function”. Though the concept is not unique to algebra, algebra helps us know how to work with functions. Usually, a function is denoted like this:

Where

- is the function

- is the input

- is the output

When speaking out loud, you would say that “WYE is equal to EFF of ECKS”.

The notation is an abstraction - it hides the details of what is happening to behind some function which we have named .

might mean “calculate the square of the input”. In this particular case, our equation becomes:

Here, is just the name for the transformation which is mathematically described by the act of squaring , which in turn is denoted as , the result of all of which is described by the variable .

Take a more concrete example with multiple inputs. For those of you who are not familiar, Sir Isaac Newton developed a set of laws of physical motion. They describe how bodies of mass move through space. Newton’s second law is often introduced in its 1-dimensional formula form:

Where

- is the mass of the object in kilograms ()

- is the acceleration of the object in meters per second squared ()

- is the force required to cause that mass to accelerate at that rate. Force is measured in units of Newtons ()

This law defines a function with two inputs - mass and acceleration. It describes what sort of force is needed to cause a given mass to move with a given acceleration. This could be useful to determine how much force your drivetrain is exerting on your robot when you measure how fast it moves across the field.

In particular, the function described by Newton’s second law is simply that multiplying acceleration and mass together produces the required force (when proper units are used). This is admittedly a trivial calculation, but not an unimportant relationship. We use it here for its simplicity, and also because it will come into play later.

Note that since only and are on the left hand side of the equation, you could hide the left side behind the function notation. In this case:

The laws of algebra allow us to re-arrange the numbers. Let’s assume we divide both sides of the equation by the variable . This results in the following:

We now have a new function which describes what acceleration should be expected when a force is applied to a mass. This might be useful if you have a pneumatic cylinder pushing with some force on a heavy gamepiece, and want to know how quickly your gamepiece will be moving!.

Admittedly, this is not a particularly deep conclusion. It’s simply an illustration of how algebra concepts dovetail nicely with concepts of abstractions and functions.

Note this is a very computer-science oriented approach to using equations and variables. Thinking about algebra, variables, and functions in this context is a purposeful choice at this point. If you go on to study advanced mathematics you will learn new ways to interpret this notation. However, for us and for now, the most useful interpretation is computer-science related.

Trig

Trigonometry draws from the concepts of algebra, introducing some very specific functions that are useful when doing calculations with both circles and right triangles. Turns out, circles and right triangles come up a lot.

The three functions we’ll particularly point out are called “Sine”, “Cosine”, and “Tangent”. Respectively, they are denoted:

Where

- is an angle in radians

Note is the greek letter “Theta” (pronounced THEY-ta). It’s just a variable, like , and in this case, an input to our new function friends sine, cosine, and tangent. Turns out in math there are certain traditions. Since the input to sine, cosine, and tangent is an angle, and angles are generally denoted with a handful of greek letters, we’ll use as the variable for now.

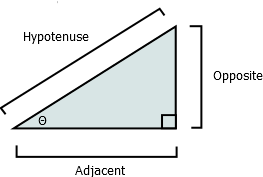

The sine, cosine, and tangent are functions that provide the relationship between an angle in a right triangle, and the ratio of the lengths of the sides of the triangle. The sides are given 3 names:

- The longest side is always the hypotenuse. It is always opposite from the right angle in the right triangle.

- The side touching the angle in question is the adjacent side.

- The remaining side is called opposite side.

The length of the sides will be denoted with the variables , , and . Under these conventions, our functions allow us to relate the ratios of lengths of sides of a triangle to the given angle with the following relationships:

Teachers commonly assist students in memorizing these relationships by introducing them to our Native American friend “Soh-cah-toa” (pronounced so-ka-to-ah). My teachers taught me the phrase “Some Old Hippie Caught Another Hippie Tripping On Acid”. To each their own.

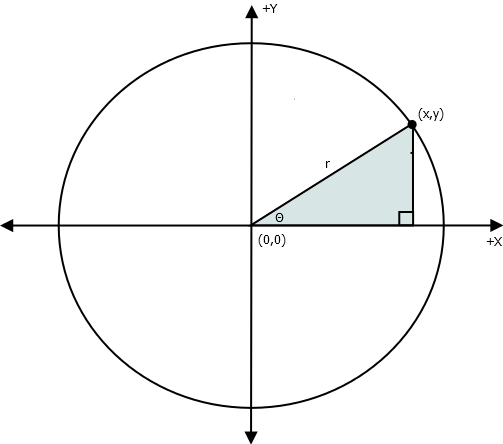

Although it may not be obvious from first inspection, Sine/Cosine are very useful in determining X/Y coordinates of a point on a circle, when given a certain number of degrees of traversal around that circle.

Note, as above, a right triangle can be drawn with one point on the origin , the other on our point of interest . Given the angle referenced from the positive X axis, sine and cosine can be used to deduce the X/Y coordinates:

Think about how this might be useful. Say you have a simple arm that rotates to raise and lower the end affecter. The length of the arm is . The axis of rotation (shaft that supports the arm) goes through the origin. Say you want to calculate how high the arm will raise up when driven through 45 degrees of rotation.

This is the same problem as above! Yay, we already know how to solve it!

Think about how high up and down the arm will be as it rotates around in a full circle. First it goes up, then back down, then up again…. If you were to plot it out, it would look something like this:

source: giphy.com

source: giphy.com

Note the periodic nature of this function - the value of the output goes up and down as the angle goes around the circle, with a repeating pattern. The patter repeats once every time the angle crosses the positive X axis.

This repeating, wave-like nature is actually quite deeply meaningful. But we’ll leave that for another post.

Next Steps - Where are we going?

Keep cranking on the math, there is more to learn! Go check out Math Primer, part 2.