Representing Ideas with Symbols

Consider the following:

When you read that, what did you think? You probably said “sixteen” in your head, assuming you think in English. This is a very good answer.

What is “sixteen”, though? It’s a number, that’s for sure. It’s also an idea - a concept.

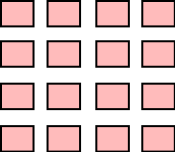

Here’s what I think of when you say “sixteen”:

Sixteen represents a quantity. There are sixteen boxes.

No, Picard, there are 16 boxes.

We are using the sequence of symbols to represent this quantity. You’re already very familiar with how this works, but it’s important to dig into the details - it will lead us to a natural way to define the binary system used in computers.

There’s two things to take away from the symbol sequence :

- It uses two symbols, and , anchored around the decimal point

- It puts them together in a particular order to give meaning to the quantity. and are not the same.

The number system we’re talking about is commonly referred to as the Hindu-Arabic number system. It was invented in India in the first century, and quickly its way through the Middle East and into Europe by the Middle Ages.

It has a particular advantage over predicessor methods for representing numbers in two ways:

- There is a limited set of symbols to remember. For most modern mathematics, there are 10 symbols - , , , , , , , , , . Each represents a particular quantity.

- The symbols are combined to represent quantities beyond the range of the symbol set. How it accomplishes this is really the secret sauce to the whole system.

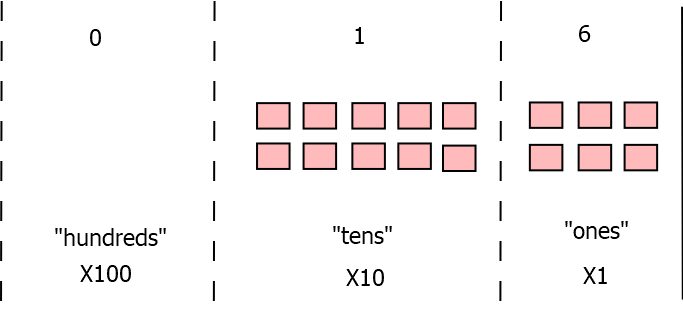

Each symbol is in some position relative to the “decimal point”. In English, we usually refer to them (from right to left) as the “ones place”, the “tens place”, the “hundreds place”, etc.

Because there is a in the tens place, we multiply the quantity represented by by ten. Then, this quantity is added in with the quantity represented by , which because it is in the ones place, is multiplied by one (aka nothing is done to it). Together, ten and six make for a quantity of 16.

The concept of “Base”

What’s the point of splitting like this? Note that any number in base 10 can be broken into a sum of its component digits.

This works, no matter how big the number gets.

Notice the pattern on the and and and such?

Here’s the takeaway: in a positional number system, any quantity is represented by a sum of the digits, each multiplied by some “potency” factor associated with its position in the sequence.

This is why we say we are using a Base 10 number system - the “base” of the number raised to some power to get the “potency” of each digit.

You can create a generic formula using a summation:

Where

- is the number of digits in the symbol sequence

- is the ‘th digit in the symbol sequence, with 0 being nearest the decimal point.

But here’s the crucial question - why is 10 the base?

There’s lots of argument as to why it is the way it is - some say because you have 10 fingers. But the Mayans used base 20 (apparently they used their toes as well?), and the Babylonians used base 60 (???). Maybe the people who liked base 10 also happened to be the best at winning wars. For better or for worse, that’s how this sort of thing often gets decided.

However, the takeaway you should have - it doesn’t have to be 10. And indeed in designing computing systems, there are better answers.

True/False

Back in the 1800’s there was this guy named George Boole was creating a mathematical computation for logical reasoning. Key to this line of thought was describing, associating, and combining the concepts of “True” and “False”. Two opposite fundamentals. Two. Hey, maybe Two is a good number.

Two is also a nice “minimum viable product” for a set of symbols. Let’s think about what you can express using numbering systems that have varying numbers of symbols:

The zero-symbol system

This system does not let you even write anything down. It is useless. Let us not waste another moment considering this.

The one-symbol system

This is effectively talley marks. Fair enough that it lets you start to express some ideas. However, you have to draw exactly the same number of symbols as the quantity you wish to express. You haven’t really gained anything here. If you already have sixteen boxes, do you need to draw sixteen lines somewhere to indicate that you have sixteen boxes? Seems sort of redundant. Why not just go out and count your boxes, and save the time of writing the talley marks? Maybe if you want to keep your own records. But then the other cavemen just make fun of you for being a nerd.

Strictly speaking, this isn’t a positional number system, since the position doesn’t matter ().

On the upside, addition just becomes string concatenation.

We need to go one higher to realize the benefits of the positional number system.

The two-symbol system

Let’s use this one.

True/False in Circuitry

Unfortunately for Boole, electricity wasn’t fully understood yet - certainly not to the point where people were looking for creative ways to harness it. The “algebra of logic” portion of his work didn’t realize its full potential during his lifetime. It wasn’t till the 1930’s that another fellow by the name of Claude Shannon realized that these True/False concepts could be mapped to voltages and currents, and controlled be switches. As part of his Masters thesis, he showed circuitry that could perform the calculations described by Boole and his contemporaries.

The idea was extremely valuable. Perhaps not revolutionary - folks had been fiddling with analog devices that could do math, and later attempted trinary (base 3) and other exotic computer formats. However, the simplicity of designing circuits which only interpret “Voltage” or “No Voltage” has made such two-state designs far superior to any other option. Especially after the invention of the consumer-ready transistor later in the 1940s and 50s, true/false was here to stay.

For this reason, almost all modern computers do math and logic using a base-2 system.

Until we get to quantum computing. At which point, I’ll have to write another blog post.

Math and Conversions in Binary

The formula for a number’s value is:

Where

- is the number of digits in the symbol sequence

- is the ‘th digit in the symbol sequence, with 0 being nearest the decimal point.

- is the “base” of the number system.

Since we’re using base-2, the formula becomes

Let’s take a quick example of a binary number:

Note the trailing for the anchor point - usually it’s left off, so we’ll start to do that here.

What quantity is ? let’s plug and chug with our formula from above. The summation would unroll to:

Which simplifies down to:

There we go! A first conversion from binary to base 10!

If you want to go back the other way, all you have to do is decompose a base-10 number into powers of two. I’ll just write out the algorithm here, and then leave it as an exercise to the reader to attempt:

- Start with your number being the number to convert.

- Find the largest position such that is equal to or less than your number

- Place a 1 in this position.

- Subtract 1 from ., subtract from your number.

- If is not yet zero, go to step 1.

What I find super slick about this is that since binary is also a positional number system, just like the base-10 one you’re used to, all the arithmetic tricks and algorithms you learned in first through third grade still apply! Adding by lining up the digits, carrying spill-over to the next place, subtraction with borrowing, even long division - they all still work!

A note on Notation

There are a lot of notations used “out in the wild” to indicate what base number system you are using. If you see a number, it’s sometimes safe to assume base 10, but sometimes not.

There are 10 types of people in the world. Ones who understand binary, and ones who don’t

Let’s not let this T-shirt prophecy come true.

Little subscripts on a number indicate it’s base. So is Ten. is Two. is one hundred, while is four. Obviously, something like is nonsense and meaningless, and you should tell the author right away so they can correct their error.

Representing Ideas with Bytes

We’ve shown how 1’s and 0’s can be assembled together to represent positive integers so far. This is a very very common usage within computing, and in general is the one processors are built around. However, there are a number of other options for interpreting a string of 1’s and 0’s.

True/False

We’ve already mentioned this, but the most straightforward mapping of 1’s and 0’s to some concept is simply true and false.

Usually,

- 1 -> True -> “ON”

- 0 -> False -> “OFF”

We’ll show later the reason why this interpretation is particularly powerful for making decisions and calculation.

Just like a single base-10 number is often called a “digit”, a single boolean 1 or 0 is called bit

Positive Integers (continued)

Vocabulary

Also as we just showed above, positive integers can be calculated by treating 1’s and 0’s as a base-2 number system. This covers a big chunk of the things we want to represent.

It’s also convenient to group sets of 4, 8, 16, 32, or 64 bits into integers to keep track of them easier - even if you are not necessarily trying to represent a number. It’s all 1’s and 0’s at the end of the day, so whatever representation makes life easiest, use that one!

In general, 8 bits is referred to as a byte. Because computer scientists are often cute, they call 4 bits a nibble.

Most modern computers work will do computation on more than one byte at a time. A word is a set of one or more bytes, which the computer works on at the same time.

Within a word, bits must be ordered. The bit closest to the “anchor point” in the “ones” position, is called the Least Significant Bit or LSB. The bit at the opposite end, furthest from the decimal point, is called the Most Significant Bit or MSB or leading bit. Note that similar acronyms are also applied to the first and last byte of a word, so you may need some context to figure out what the author refers to. Capital letter B often means byte, lower-case letter b often means bit.

Historical Perspective on Byte Width

Tiny embedded processors are often still 8-bit (one-byte word). For many years, 32-bit computers (4-byte words) were the standard. Within the last few years 64-bit (8-byte) words has become standard. Later blog posts will delve further into exactly what this implies, but for now just think of it as “how many bits can the computer work on at once”.

Special-purpose computers can have more exotic word-sizes. The older Nintendo 64 gaming console was one of the first instances of using 64-bit processors in consumer devices, and that was back in the early 1990’s. Even before that, 24 bit processors were common in some audio applications, as 24 bits was considered “good enough” to represent audio that humans could hear. Graphics processing frequently goes big - some bleeding edge graphics cards have parts that work on 512 bits at a time!.

If you use every bit in a word to represent a positive integer, there is a fixed range of numbers you can represent. All bits off of course corresponds to a value of . For an bit word, all bits on represents a value of (proof left as exercise to the reader). For example, a 32-bit integer can represent values between 0 and 4294967295. It’s a really big range, but it’s not without its limits!

When you treat a set of bits as only positive integers, you are said to be doing unsigned math.

Negative Integers

Representing negative numbers in a nice way is a bit of a challenge. The truth is you could pick any scheme you want to map sequences of 1’s and 0’s to numbers, but you want to do it in a way that makes calculation easy. If you had to hard code every combination into your software, you’d get tired and frustrated pretty fast. A healthy dose of laziness is the mark of a good engineer.

The good news is that the most commonly used system is pretty darn good. It’s called Two’s Compliment. We won’t delve too much into it, but suffice to say it has the following properties:

- The Most Significant Bit represents the sign of the number. 0 means positive, 1 means negative.

- When the leading bit is 0, bits are interpreted the same way as unsigned integers.

- When the leading bit is 1, for an N bit number, the value is equal to where is the unsigned value of the first bits.

Therefor, a 2’s complement number will have range to . Proof is again left as an exercise to the reader.

For example, when ,

| Base 2 | Base 10 |

|---|---|

| 01111111 | 127 |

| 01111110 | 126 |

| … | … |

| 00000010 | 2 |

| 00000001 | 1 |

| 00000000 | 0 |

| 11111111 | -1 |

| 11111110 | -2 |

| … | … |

| 10000001 | -127 |

| 10000000 | -128 |

The key advantage of doing it this way is spelled out in more detail on wikipedia. In short - addition and subtraction just work, without anything special. If you add up -1 and 1, and allow for the carried bit to “fall off” the end of the 8 bit calculation, you get 0.

As you maybe already see, the 2’s compliment pattern is technically circular when the bit width is fixed (as it is in all processors). When you are working with 8 bit integers, and add 1 to 127, in bits, you get . This is often called overflow or wraparound. It’s unintuitive at first, but usually indicates a problem with your software - adding two positive numbers should not create a negative one. Some processors can detect this and raise an alarm.

When writing software and designing hardware, use caution when depending on rollover behavior. It’s not always obvious without sufficient documentation, and if anyone accidentally changes variable bit width in the future, they’ll be in for a world of hurt figuring out why the code doesn’t work anymore.

When you treat a set of bits as 2’s compliment integers, you are said to be doing signed math.

Fractional Numbers

Most engineering values in the real world aren’t nice round integers. We need a way to represent some value like . In broad strokes, there are two ways this is accomplished.

Fixed Point

Fixed Point is largely the historical way that fractional numbers were represented. There’s some more formal math that goes into it, but the best way I know to think of it is that each “bit” represents some fraction of an engineering unit. For example, you could say that a particular variable is scaled at “0.25 RPM per Bit”, implying that the real-world engineering value is always equal to 1/4th the value of the integer you read in software.

This makes it very easy to store a fraction - it’s no different than a normal integer. The only thing to be careful of is when you store, read, or perform math with the stored value - you have to be careful to build in additional conversion factors to make your formulas work properly.

This small bit of extra math can easily be optimized at build time though, so the method is still quite low overhead at runtime. For this reason, it’s usually the best choice when execution speed is of the utmost importance on resource-limited embedded processors.

As you can probably see, there is an obvious limit to the size of the “step” you can represent. In our above example, we can exactly represent a reading of 7.75 RPM, but not 7.8 RPM. The more granularity you desire, the less min/max range you get.

Floating Point

Floating Point is the “newer” way to represent fractional numbers. Floating Point is covered by IEEE standards documents, which show how to split a number into an exponential representation, then pack it into bits. Again, the mapping is chosen carefully to make the math easy to do while a program is executing.

Floating point is still pretty complex to do by hand. Most modern processors include hardware units to support doing the math. These are not quite as fast as doing integer math, but are far faster than doing it “long hand” within your software implementation.

Due to the proliferation of floating point support in hardware, it’s becoming more and more the standard for how to do engineering math in embedded systems. For FRC robotics purposes, I would recommend using it. Only in cases of extreme optimization does it make sense to go back to using fixed point (or other) representations. However, keep in mind that it does bear a small performance penalty - try not to use floating point math for doing things like counting, where the fractional portion will never be needed.

Letters

Beyond numbers, there are a lot of other things you might want to represent. Letters are a common one - any time you print something to console, you have to represent a string of characters that forms English words that some human can understand quickly.

To do this, there was again a standard, called ASCII, put together to map sequences of bits to letters in the alphabet. They started with just the common English/Latin characters, plus a handful of helper symbols and codes designed around how typewriters printed out letters (see Carriage Return and Line Feed). Later standards like UTF-8 and similar expanded upon this, and continue to expand to get more and more languages and systems of writing represented and displayed in computer systems.

Conclusion

We’ve done an overview of some of the methods used to map 1’s and 0’s to various ideas. Going forward, just keep in mind that there exists a number of ways to transform a sequence of 1’s and 0’s into numbers, fractions, letters, and beyond.

There are 10 types of people in the world. Ones who understand binary, ones who don’t, and ones who don’t expect base-3

Next Steps - Where are we going?

We know some basics about the nature of 1’s and 0’s. Next, we’ll learn how to combine them together. Check out Boolean Logic for more details!