C is quirky, flawed, and an enormous success. - Dennis Ritchie, co-creator of the C programming language.

Introduction

In this post, we’ll explain the basics of the C programming language syntax, showing how it accomplishes the major goals of any high-level programming language.

The “C-like” Syntax

Though we’re about to describe software syntax for the C programming language, the implications of these facts and examples are much broader.

Many of the concepts C introduced in how a high-level language is to specify program behavior were inherited into other programming languages. For this reason, many languages are said to have “C-like syntax”, meaning that the fundamental way you specify behavior follows lots of the same design patterns laid out by C. The lion’s share of commonly used programming languages follow these patterns, so it seems to be a good place to start!

For most of the readers of this blog, I’m assuming you have some casual familiarity with how to write software. But even if not, don’t worry - we’re going to go through the basics, again using a ground-up format to explain how computer programs are put together.

Storage of Source Code

C code source files are just plain-text, ASCII or utf-encoded text files, which just happen to have extensions like .c or .h. They can be opened and edited by any text editor: VS Code, Notepad++, VIM, Emacs, even the built-in Windows Notepad (not recommended).

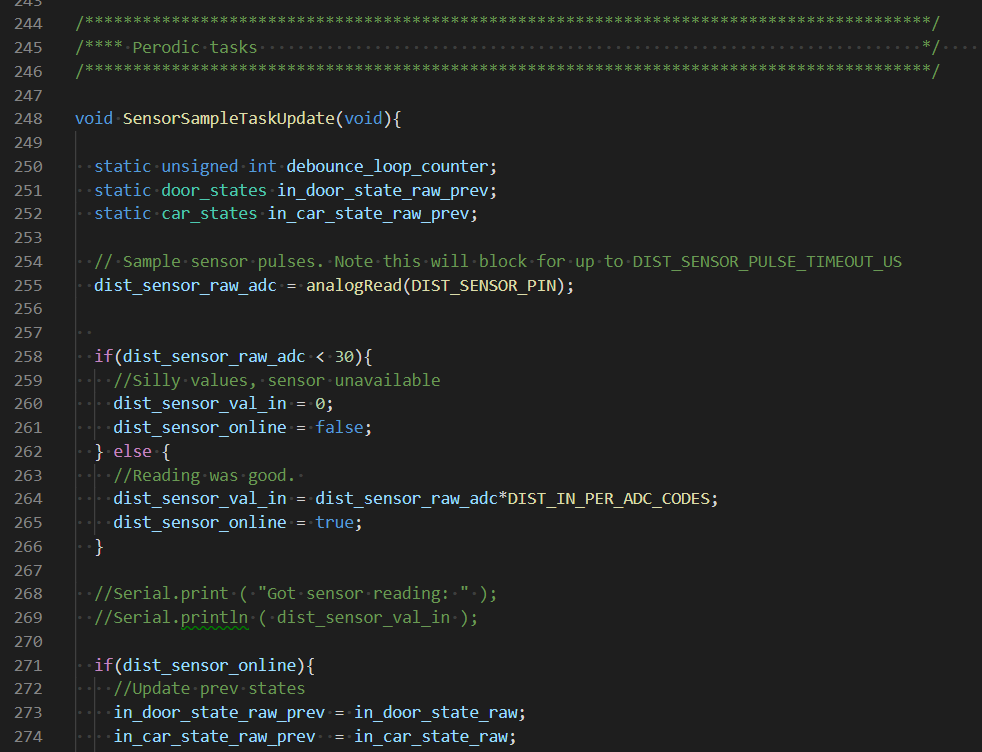

A word to the wise - choose a good text editor which knows about C code syntax, so it can properly highlight different parts of each line. These visual cues are invaluable as a software developer to visualize the behavior of your code.

C Code Statements & Their Components

Programs are fundamentally built up of a series individual statements. Each statement may contain directions to perform one or more of the common abilities of programming languages.

Every statement has some content, and is terminated by a semicolon (;). It’s just like putting a period at the end of your sentences. We use semicolons instead of periods because some numbers have periods inside them (ex: 3.14159), and using a unique symbol for unique meaning is easier than having to use the context around the symbol to determine meaning.

Here is an example of a simple statement:

result = 3 + 5.7 * input;

We will use this for reference as we go forward in the next few sections.

Constants

C syntax allows software writers to use numbers in statements. THese numbers can be simple integers, like 3 in the sample statement. They can also be fractional or floating point numbers, such 5.7 in the sample statement.

A single negative sign (-) in front of a number will of course make it negative - -26 is an allowed constant, equal to negative twenty six.

Variables

C syntax also allows you to define names for memory locations. By using the name in a statement, the contents of that memory location will be used. Since a memory location can generally hold a range of numbers, these named memory locations act just like the variables in algebra. Therefor, we call them variables

In the statement above, input and result are both variables.

Note that C does not allow variables to simply come into existence and disappear at runtime - each variable that is required must be declared prior to usage. The precise manner in how you declare the variable will dictate how many bits are used to store values, whether the value is read/write or read-only, which portions of code are allowed to access the variable, and a whole slew of other properties.

Built into the C programming language are a few basic variable types:

int is the basic integer storage. It is interpreted as a 2’s compliment signed integer.

char and short both store integers as well, but take up fewer bits than int (and therefore have a more restricted range).

long will also be an integer, but take more bits than int (and therefore have a wider range`).

char is usually treated as unsigned by default. Any type can get the qualifier unsigned put in front of it to force it to be unsigned.

The exact number of bits for each of these is not fixed - it depends on what type of processor you are on. This is incredibly horrible when attempting to write code that works the same on multiple machines, so other types like int8_t, int16_t, and int32_t are actually better to use - these explicitly specify the bit width.

double and float are both floating point representations, allowing you to store decimal values.

A number of other types are built in, and the keyword typedef even allows you to define your own!

Assignment

Once we have variables, we have to have a way to get information into them. In C code statements, the = equals sign character is used to perform an assignment operation. Assignment takes whatever is on the right-hand side of the =, and places it into the variable on the left-hand side.

It’s roughly equivalent to a “store” operation, rather than an expression of equality (more on that later). Think of it as memory movement - you do some calculation to get a number. Then, the equals sign indicates the calculation’s result needs to be stored somewhere. The variable on the left hand side provides the memory address where the value is to be stored at.

In the sample statement above, the value calculated on the right-hand side of the = is being stored into the variable named result - and by this, we really mean the value is being put into the RAM memory bits associated with the variable result.

For example, combining our knowledge of Variables and Assignment:

int var1 = 25;

int var2 = -32;

char var3 = 128;

double var4 = -534.574029;

unsigned int var5 = -23; // Will do weird stuff.

short var6 = 67.5; // Will also do weird stuff.

Operators

On the right-hand side of any = sign is a set of operations which perform the actual calculation of interest. C syntax reserves a set of characters for performing this calculation. There are a few broad categories of Operators.

Combining Numbers with Math

Some common math functions are implemented:

+adds the thing on the left and on the right of the symbol together*multiplies the thing on the left and on the right of the symbol together-subtracts the thing on right from the thing on the left of the symbol/divides the thing on the left by the thing on the right of the symbol

In the example above, the statement says to first multiply the value stored in the variable input by 5.7, then add 3 to the value. Finally, as already mentioned, that calculated value gets stored in result.

Normal order of operations does apply here (mult/div, then add/subtract). Parenthesis ( ) can be used to group operations if a different operation order is required.

For example, the statement result = (3 + 5.7) * input; simply multiplies input by 8.7.

There are some “specialty” math functions that C also defines. These aren’t strictly necessary, but provide useful shortcuts:

variable++will change the value stored invariableby adding 1 to it. This is called “incrementing” the variable.variable--will change the value stored invariableby subtracting 1 from it. This is called “decrementing” the variable.- Note

++and--operators perform an assignment without an explicit=. This is different than other math operators.

- Note

- The

%symbol is called the modulo operator - it calculates the remainder after division.- For example,

7 % 5equals to 2 (since 7 divided by 5 is 1, remainder 2).

- For example,

Combining Bits with Boolean Logic

C syntax also allows you to perform the basic boolean operations we described earlier. Just like regular math, special symbols are reserved to indicate the operation.

&&performs the AND operation between two values||performs the OR operation between two values|is the symbol on the key right below backspace, accessed when you hit shift.

!performs the NOT operation on a single value

All of these are called the “Logical” operators, since they treat their numbers like a single boolean value. The reason we say “treat” is because C doesn’t have a dedicated “boolean” type - the best we can do is just use one byte (named char, as we will see later). Given these bite-sized variables, the value of 0 is treated as FALSE, while any other value is TRUE. As it turns out, these are the more commonly used set of boolean operators.

Lesser used, but worth a mention, are the bitwise operators - they do the same boolean operation, but work bit-by-bit on the number. For example, the bitwise-NOT of 0b1100 is 0b0011 (note how each bit is flipped to the opposite value). Similarly, the bitwise-OR of 0b1100 and 0b0101 is 0b1101 (each bit in the first number OR’ed with the corresponding bit in the second number).

&performs the bitwise AND operation between two numbers|performs the bitwise OR operation between two numbers~performs the bitwise NOT on a number.

See examples of the usage of these things later on. The key for now - these operators provide ways of combining boolean values to create new boolean values.

Creating Boolean values from Numbers with Comparison

Just like in math that you’ve probably done in high school, there are a set of operators that will do comparison between two integer numbers to create boolean values. These operators do almost exactly what you would expect:

>and>=check if one number is greater than (or equal to) another number.<and<=check if one number is less than (or equal to) another number.==will check if two numbers are exactly equal!=will check if two numbers are not equal

Note this distinction between the action of = and ==, it’s a very common thing that gets lots of new software developers. = performs assignment - it takes one number and stores it into a memory address. == performs comparison - it checks whether two numbers are equal or not, creating a boolean from the result.

Comments

Some special statements are called comments. These are wrapped in special characters that tell the compiler to completely ignore the statement. The statement is only there to help human beings.

// Some comments begin with two slashes

/* Others are between slash and star sequences */

Put comments wherever you want to remember (or tell the next developer) what your code is doing. Use comments to describe the “why”, and not the “what”.

Grouping

A flat list of instructions is just fine for a computer, but generally humans like to visually organize their code a bit more. Therefor, in most programming languages, statements are grouped together into clumps called blocks based on the functionality that is desired.

Blocks

A block of code is simply a logical subset of statements which form one cohesive action, and are meant to be run together. Which statements belong together and why will be discussed in due time, but for now consider just that statements will be grouped into units called blocks.

C code uses the symbols { and } to mark the start and end of each block. By convention, the contents of the block are indented with whitespace by some amount (the author is a strong advocate for 4 spaces).

{

// This is the start of a block

// Here is some code

var = 25*input;

output = var & 0b00001111;

// This is the end of a block of code.

}

Note that multiple blocks can be nested together:

{

// start of outer block

{

// Inner block 1

}

{

// Inner block 2

}

// end of outer block

}

Blocks are used to group pieces of code together to defining when certain parts of logic should be executed or skipped based on conditions (conditional flow), or for doing a chunk of code multiple times (Releating Flow).

Grouping for Conditional Flow

In C, you can use a set of statement as a prefix to a block, to define conditions on which the block should be run. The prefix statement must use some value or quantity that resolve to a boolean. Then, when the boolean is True, the block is executed. Otherwise, the block is skipped.

The basic syntax for the prefix is if(<condition>) { <code to execute> }. For a more concrete example:

int condition = TRUE;

if(condition){

// This code will be run.

}

condition = FALSE;

if(condition){

// Now this code will be skipped.

}

C also provides a few other tools for making more complex combinations of these if- blocks. The else statement is the alternative to if - when if’s condition is false, then the code for else is run instead. Concretely:

int condition = TRUE;

if(condition){

// This code will be run.

} else {

// This code will be skipped.

}

condition = FALSE;

if(condition){

// Now this code will be skipped.

} else {

// and this code will be run.

}

There is one more construct, which allows you to stack many if statements together, if the conditions should be mutually exclusive (zero or one are true), or a priority is needed (if multiple conditions are true, only one is acted on).

int condition1 = TRUE;

int condition2 = TRUE;

if(condition1){

// This code will be run.

} else if(condition2){

// This code will be skipped, since we "hit" the condition1 statement first.

} else {

// This code will be skipped.

}

condition1 = FALSE;

condition2 = TRUE;

if(condition1){

// This code will be skipped

} else if(condition2){

// This code will be run

} else {

// This code will be skipped.

}

As we go forward we will see more and more practical examples of this usage, so don’t worry too much about understanding the nuance and memorizing it now. Just keep in mind that there is a construct that uses if to control if certain pieces of code get executed or not!

Grouping for Repeating Flow

The other common usage for grouping blocks of statements is for when you want to have a chunk of code repeat many times over and over. Admittedly this is less common for robots, but still happens. As a simple example, say you had 20 numbers you wanted to print to the screen - using loops, you can use the same print code many times, minimizing the amount of copy/paste or rewrite work you have to do.

A block of code which is run many times over and over is called a loop. There are two main types of loops available in C.

The while loop repeats a chunk of code so long as a condition is TRUE. The syntax used in C is while(<condition>) { <code to repeat> }. In a more concrete example:

int condition = TRUE;

int counter = 0;

while(condition){

//Code to repeat

if(counter >= 10){

condition = FALSE;

} else {

counter++;

}

}

If you trace the code execution, you should see that the code on the inside of the while loop runs until our counter is 10 or larger. THe counter starts at 0, and gets incremented every loop until we exit.

The condition of counter >= 10 is referred to as the terminal condition of the loop - it’s the condition which triggers the loop to stop running, and allows execution to continue past the final } of the block.

Now, of course, condition doesn’t have to be tied to a fixed number of loops - it could be some event on the robot (like receiving a packet over ethernet) or user interaction (driver pushes a button), for example. But for when you are looking to run for a set number of loops, there is a syntax which allows expressing it more concisely.

Enter the for loop in C. It looks way more complex than it actually is. For loops are used when you know the exact number of times you want to iterate, rather than simply wait for some external event (for an unknown duration).

Just like while loops, for loops cause a block of code to get executed many times. The prefix to that block has extra syntax to provide a concise way of describing how long you will loop for.

This syntax is for(<init action>; <loop condition>; <loop action>){ <Code to be executed> }. THe Init action is simply a statement to be done right before starting the loop, and the loop action is a statement to be run at the end of the loop.

99% of the time, for loops will be written something like this:

int idx;

for(idx=0; idx < 10; idx++){

// This code runs 10 times

}

The sequence of steps that is summarized all in that one line:

- Before running anything inside the loop,

idxis set to0 - Every loop, before doing the contents of loop, we check if the condition

idx < 10evaluates to TRUE. This happens for the first 10 loops, but not for any subsequent one. - After running the contents of the loop, we perform the action

idx++, which keeps idx up to date with the number of times we have completed the loop action.

In C, the for loop is pure syntactical candy. There’s no reason you can’t do the exact same thing with a while loop:

int idx;

idx = 0;

while(idx < 10){

// This code runs 10 times

idx++;

}

However, that takes two extra lines. Since this pattern is very common, the C language built in the for loop shortcut.

We’ll get into more of the nuances of how to make the choice between for and while in future posts.

Grouping for Reusability

Another major usage of blocks of instructions is to create reusable chunks of code which perform a specific subset of functionality. In C code, we refer to such blocks of code as functions. A function is simply a block of code with a specific prefix to create the name of the function, specify what inputs it has (the arguments), and define the type of output (the return value) it has.

Generally, the syntax for creating a function is:

<return type> <function name>(<arguments>){ <contents of function>}

Functions should generally perform one monolithic task, and one task alone.

For example, let’s create a function with calculates the square of some input number, but preserves the sign of the number. This is a common operation done while conditioning joystick inputs from a driver - it gives them less sensitivity near the center for precise slow motions.

double squareSigned(double in){

double result;

result = in * in;

if(in < 0){

result = -1.0 * result;

}

return result;

}

In painstaking detail, here’s what the handful of lines of code actually mean:

- The function is first declared.

double squareSignedsays “There is a function namedsquareSignedwhich returns a value of typedouble”. squareSigned(double in){says “FunctionsquareSignedtakes one argument namedin, which must be of typedouble.- Whenever

squareSignedis run, the first step is to set aside some memory to keep track of the result while we’re performing the operation. We’ll refer to that memory with the nameresult, treating it as a double floating point value. - The first real step calculation is to multiply

inby itself, and store that intoresult. - After we have the value of

in * instored intoresult, we now need to re-apply the sign ofin(since squaring it always produces a positive value). - We calculate whether in was negative or not by comparing it to zero with the statement

in < 0. - If

inwas in fact negative, we also need to makeresultnegative. To accomplish this, we use the if statement to conditionally run our negating logic. - Within the

if(){block, multiplyresultby negative one, and store it back into result. This means thatresultwill now have the same sign asin - Finally, we specify that the value in

resultis to be the return value of the function. With the statementreturn result;, we return execution control to whatever chunk of code called this function in the first place, returning the value fromresultat the same time.

Finally, keep in mind this is just one basic, contrived example, targeted at the first-time learner. We’ll get more into the “when” and “why” of function usage in later posts, but for now, just remember that such a tool for reusing functionality is available in any programming language worth its salt.

Miscellaneous Code Examples

Boolean Values

A very common use-case of the bitwise operators is forcing a single bit to 1 or to 0 in a number. For example:

//Force the least-significant bit of value to 0, but leave the rest untouched.

value = value & 0b11111110;

//Force the least-significant bit of value to 1, but leave the rest untouched.

value = value | 0b00000001;

Another usecase is to check if a particular bit is 1 or 0:

// Check if the most-significant bit is set to 1

bit_is_set = value & 0b10000000;

if(bit_is_set){

// bit was 1

} else {

// bit was 0

}

In this example, the constant 0b10000000 is referred to as the “bitmask” since it masks off all bits except the first one (aka forces the to 0). This way, if the top bit is zero, bit_is_set will be non-zero, and can be used in the if() statement to change the action of the program.

Using Functions

Consider the squareSigned() function we looked at earlier. Back in main robot code, this would get used in a fashion something like this:

// ...

double joyValue;

double motValue;

joyValue = getDriverXJoystick();

motValue = squareSigned(joyValue);

setLeftDriveMotor(motValue);

setRightDriveMotor(motValue);

// ...

In this highly contrived example, we declare two variables to store the value of the joystick, and the value we want to power the motors at. We’ll assume that functions named getDriverXJoystick() and setLeftDriveMotor() and setRightDriveMotor() exist and have been provided to us for interaction with the physical hardware. Our job is just to hook up one piece of hardware to another.

Since this isn’t the only joystick on the robot, we’ll use our common squareSigned() function to perform the desired mapping from a joystick reading to a motor command.

In this example, we first populate our joyValue with some value read in from the joysticks.

We then pass that value into our function squareSigned(), which transfers control of the program to that function. When the function is done with its transformation, its return value is stored into our variable motValue. We can then use motValue as the command to send to both motors.

Note that for these examples, we’ve chosen some very obvious names for our variables. Clearly, to any reasonably astute observer, joyValue would tend to imply something along the lines of “value from a joystick”, and motValue would imply “value for a motor”. This is intentional - choose meaningful names so its easier for you to remember exactly what each variable is for, when you come back and look at the code in 5 weeks and have no idea what it was doing.

Of course, the compiler is not a human, and doesn’t know that the string of characters joyValue has any real relationship to a joystick. No matter how good of names you choose for your variables, the compiler will still always expect you to populate them with meaningful values yourself - ie, call getDriverXJoystick() and assign it into joyValue. The above code could be written as:

// ...

double woodieFlowers;

double deanKamen;

woodieFlowers = getDriverXJoystick();

deanKamen = squareSigned(woodieFlowers);

setLeftDriveMotor(deanKamen);

setRightDriveMotor(deanKamen);

// ...

And it would work the exact same way. The only difference is you’ll be hating yourself in three days when you have no recollection what a woodieFlowers is for.

Next Steps - Where are we going?

We’re nearing the end of the story-arc for our introductory content! Next up, we’ll start exploring how these basic C constructs are accomplished on a real processor. This will be the last major building block in understanding, at a high level, how lines of code actually perform their action under the hood. To get started, check out our introduction to the x86 assembly language!